Three Christmases

December 20, 2020

In the Bible, we have three different version of the birth of Jesus.

In the Gospel of John, we have a Greek hymn to the Logos or Wisdom ( personified in the Old Testament as a companion of God since the beginning of time) adapted by the Evangelist to provide an explanation of how the Word of God became a human being in the person of Jesus; born through the will of God to bring Light and Truth and the opportunity to become ‘children of God’ to all who believe.

The writer of the gospel of Matthew took themes from the lives of Old Testament leaders such as Joseph (the dreamer) Moses, Samson, Samuel and David, and from the writings of prophets like Hosea and Isaiah to create the tale of the birth of Jewish Messiah. Born in a house in Bethlehem (like David) he will become a saviour, like Moses; a judge and a Nazarene, like Samson; coming from the dynasty of David, he will be King of the Jews. As the prophets and psalms predict, the wise and powerful of the pagan world will come from afar to pay homage to him. They will be drawn to his light in the form of a rising star and will offer him gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Matthew’s Jesus is the fulfilment of all these Old Testament traditions. Like the Jews of old he has to flee from troubles in his homeland into Egypt, and then returns to live in his homeland, but not in Judaea, but in Nazareth of Galilee.

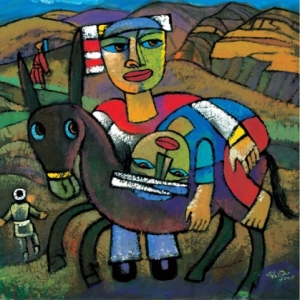

We get a very different story of the birth in Luke’s Gospel. Jesus’ parents come from a provincial town, from a region despised as semi-pagan by the religious leaders. They are humble folk, pushed around by the Roman authorities, forced to leave home to register for a census when Mary was heavily pregnant. They were not important or wealthy enough to be given a guest chamber, so her baby was born in the lower part of the house, where the animals were brought in from the cold, and her baby was placed in a manger. The news of the birth is given first to more outcasts – shepherds, keeping watch over their flocks on the hills outside Bethlehem (as King David was doing when Samuel summoned him to be anointed as the next king of Israel). They are the ones who recognise him as King and Messiah, as do other poor and despised people like Elizabeth and Zechariah, Simeon and Anna. In Luke’s tale, the birth goes unnoticed by the rich and powerful – there are no wise men, no star, no slaughter of babies in his story. After the purification, the family goes peacefully back to Nazareth, and Mary ponders all that has happened in her heart, as Luke means us to do.

There are some themes in common to all three stories; they hint at a virginal conception to make the point that the birth marks a new spiritual beginning for the whole human race; and they tell us that the people who accepted this child as the Messiah were those outside the religious mainstream: people from the provinces, the poor, shepherds and pagan astrologers.

Over the years, many more have elaborated the story. New Testament writers, theologians, composers of hymns and carols, artists, authors of mediaeval mystery plays, and folk stories, all have added their own interpretations, some of which have become part of the main story for us. Even saints have done their bit, like St Francis, who gave us the crib scene, with the stable, the ox and the donkey, none of which are mentioned in the Gospels. The birth of Jesus has been set in every place and time, until we come to the rich tapestry of the Christmas story we enjoy today.

None of this matters. God gave us his son to be born into obscurity, in a time when no official documents, like birth certificates or passports, and no technology like cameras or videos existed to record the exact details for future generations. It was as if God was saying to us: “Here is my gift to you. Take it and make of it what you want. Tell his story in the way that is most meaningful to you and your people.”

The only proviso is – don’t think (like the child in my granddaughter’s nativity who refused to have any doll but hers as the baby Jesus)) that your baby Jesus is the only proper one. Read and listen to all the accounts of the birth of Jesus, don’t muddle them up, and try to hear what God is saying to you through each different story.

Bishop Nick Baines got into big trouble with some sections of the media when his book ‘Why wish you a Merry Christmas’, was published. (That seems to be an occupational hazard of being a C of E bishop these days!) He was accused of saying that we shouldn’t sing traditional carols or have infants doing nativity plays. If you read his book (which many who commented hadn’t!) you will find he is not saying that at all. What he did write is: sing carols, enjoy them, but don’t stop there! Some of them are good theology, but some of them are nonsense – especially those that imply that the baby Jesus never cried, or that the birth was beautiful and easy and Mary and Joseph had no problems. Enjoy your children and grandchildren performing the nativity story, but don’t stop there. Don’t leave the birth story as a tale for children, like Tinkerbell or Father Christmas, to be rejected when you grow up.

Go back to the Bible and read the accounts in the gospels and think about the characters as real people with real problems. Think how difficult it must have been for Mary and Joseph to accept this child, how their lives were disrupted by his birth, how the religious people missed the point, how the news was given to outcasts and strangers, and that it was not the faithful, but the faithless who came to adore him – and meditate on what that says to us about how God chooses to be present with us in the problems and uncertainties, the disasters and messiness of real life.

Then think about what that says to us as Christians about where we are meant to be and how we are meant to live, so that we bring light and truth and love to others as Jesus did; and how we can demonstrate what it means to know that, because of this child and the man he became, we have the chance to become children of God – and so does everyone else.

That is amazing and life transforming stuff – and a very good reason to celebrate and wish everyone a very happy Christmas.

Advertisements

Occasionally, some of your visitors may see an advertisement here,

as well as a Privacy & Cookies banner at the bottom of the page.

You can hide ads completely by upgrading to one of our paid plans.

Into Temptation…

March 10, 2019

SERMON FOR LENT 1 (YR. C)

(Psalm 91, 1-2 & 9-16; Luke 4, 1-13)

When the ICET (International Consultation on English Texts) was working to translate the services of the Church into modern English, one of the phrases which caused them most difficulty was the last but one petition of the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Lead us not into temptation’.

Part of the difficulty stems from the possible meaning of the original Greek of the text in Matthew and Luke, and even of the Hebrew behind that. For instance, the Greek verb translated ‘lead’ could mean taking in an active sense, to lead by going before, or simply to announce. And depending on the understanding of the Hebrew behind this clause, again it could be active, meaning to cause something to happen; or permissive, to allow something to happen. So, the Syriac version of the New Testament translates this “Do not make us enter into temptation”.

Again, the preposition ‘eis’ and its Hebrew original could imply simply ‘into’ or ‘as far as’ but, more strongly ‘to be placed under the power of’. So, one translation could be “Do not allow us to fall under the power of temptation” that is, be overwhelmed by it.

Again, the preposition ‘eis’ and its Hebrew original could imply simply ‘into’ or ‘as far as’ but, more strongly ‘to be placed under the power of’. So, one translation could be “Do not allow us to fall under the power of temptation” that is, be overwhelmed by it.

However, the word which gave the translators most difficulty was the word translated ‘temptation’. The Greek original is found rarely in secular Greek, but very often in Biblical Greek, both in the New Testament and in the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament, with a variety of meanings. It can mean simply an attempt; it can mean a test in the sense of testing a metal or testing somebody’s competence or conviction (and in this sense it is often used of God testing human beings). It can mean a malicious attempt to trick someone, and is used in that way of the attempts of the Scribes and Pharisees to catch Jesus out by asking him trick questions. It can be used to mean the seduction into sin which is the usual modern meaning of ‘temptation’.That’s how it is used to describe Satan’s temptation of Jesus in the desert. It can mean a trial or ordeal. It can mean to tempt God. In all of these meanings, the form of noun used implies a continuing process, not a one-off event.

Some interpretations of the text are more difficult for us to accept, not because of they don’t translate the original Greek correctly, but because they run counter to our beliefs about the nature of God, and of human beings.

For instance, we believe that God is good, and wills happiness and good for human beings. So how can we even think that God would deliberately seduce us into sin or put us under the power of evil?

Secondly, it is nonsense to pray that we won’t be tempted, because temptation is part and parcel of the human condition. God gave us free will – but there would be no point in having free will if there were no circumstances in which we were tempted to choose to sin. It is a mark of being a real human being that we can be tempted to do wrong – and that is why the story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness is important: it shows that Jesus was, as Hebrews says, “one who in every respect has been tempted as we are”. (Heb. 4.15) The one difference is, as Hebrews goes on to say, “yet without sinning”.

So, if we are not asking God not ever to put us into a situation where we are tempted, and we cannot conceive of God deliberately trying to make us commit sin, what are we asking in this part of the Lord’s Prayer?

Modern translations of the New Testament have used a variety of phrases, most of them designed to express the hope that God will not test us beyond what we can cope with, or allow us to be overwhelmed by temptation.

The Good News Bible has “Do not bring us to hard testing” and the New English Bible “Do not bring us to the test”. The Jerusalem Bible has “Do not put us to the test” and the NRSV “Do not bring us to the time of trial”.

Most of the denominations have used a variation on that last phrase in their modern language  services, and pray: “Save us from the time of trial”. You will find this version in the Methodist, the URC, the Roman Catholic and other Anglican churches, such as the New Zealand Church. The Church of England could not agree to use the internationally agreed text, and kept “Lead us not into temptation” in their modern language Lord’s Prayer as well as in the traditional language one. I rather like Jim Cotter’s free modern translation of the Lord’s Prayer, which has: “In times of temptation and test, strengthen us; from trials too great to endure, spare us; from the grip of all that is evil, free us.”

services, and pray: “Save us from the time of trial”. You will find this version in the Methodist, the URC, the Roman Catholic and other Anglican churches, such as the New Zealand Church. The Church of England could not agree to use the internationally agreed text, and kept “Lead us not into temptation” in their modern language Lord’s Prayer as well as in the traditional language one. I rather like Jim Cotter’s free modern translation of the Lord’s Prayer, which has: “In times of temptation and test, strengthen us; from trials too great to endure, spare us; from the grip of all that is evil, free us.”

When we pray this petition, we are asking God to be with us as we face the everyday temptations of human life. We are asking for divine protection when we face situations where the urge to sin becomes overwhelming. We are asking for divine guidance when the prompting of our own nature, or the urging of others, bring us to situations where we may be tempted to flirt with sin. We are asking God not to abandon us when our faith, or our bodies are under assault.

When we face these situations (as all of us will) the story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness shows us how God answer this petition of the Lord’s Prayer.

We do not have to take this story literally. Jesus may have had an experience like this when he spent time in the desert after his baptism by John, but since he was alone, and the conversations went on inside his head, how would anyone else have known the details? Mark has the simple statement that ‘he was tempted by Satan’; it is only Matthew and Luke who provide details of the threefold temptations. But these are temptations which Jesus would have faced during his whole ministry, as they are temptations which face any of us who try to bring others into the Kingdom of God. So it is perfectly possible to see the story of the time in the wilderness as a word picture of the temptations of ministry for Jesus and for ourselves.

The first is the temptation to bring people into faith by providing for their material needs alone. Perhaps there are secondary temptations also; to provide the basic necessities of life, but only to those of ‘our’ faith; or the temptation, which is so prevalent in our society, to believe that the accumulation of goods will bring happiness, or is a sign of God’s favour. Jesus answers this by affirming the supreme importance of the spiritual – the Word of God – rather than the material – bread.

The second temptation is to use political power, including force, to bring people to faith. We can all think of examples of Christians giving in to this temptation throughout history – from the way the final texts of the Creeds were arrived at, to the Crusades, and the wars of religion that so disfigured Europe during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Jesus rejects this by quoting from Deuteronomy a verse that insists that worship must be given to God because of God’s character, and not in response to political power or force, which are seen as works of the Devil.

Finally there is the temptation to encourage faith by demonstrations miraculous power, which is, in effect, to tempt God. Again, we can all think of times when churches have tried to prove that they have the one true faith by appeals to signs and wonders, or miraculous cures to which they alone have access. Jesus again quotes from the Hebrew scriptures which forbid testing out God’s support in this way. During his ministry he always refused to provide miracles ‘to order’ to prove his credentials.

Jesus was saved in his time of trial, and delivered from evil because of his close relationship with God, and his total reliance on God’s love and support. Psalm 91 assures us that God’s love and support is with us through the difficult times too. For Jesus, his relationship with God was founded on his deep knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures and the tradition (in his case the Jewish tradition), his constant reference to God through prayer, and his submission to God’s will in humility.

As we face the tests and temptations of our lives, these same resources and this same relationship with God can save us too from trial and temptation and deliver us from all evil.

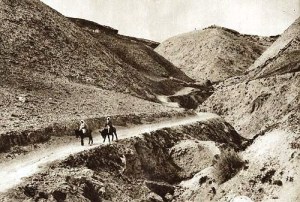

THE JERICHO ROAD

July 14, 2013

Sermon for Trinity 6. Yr. C. ( Luke 10, 25-37)

When a preacher stands up here on a Sunday morning, you have certain expectations of what will happen. If I were to start performing a pop song, or a magic trick, or threw a football into the congregation, you might think it was something to do with the sermon, but if I carried on without making a serious point, you’d be confused; and if I started to wash my hair or clean my teeth, you would not only be confused, you’d be embarrassed, and a lot of you would think “She’s lost the plot! She obviously doesn’t know where she is!”

But I do know where I am. I’m on the Jericho road – and so are you!

We all operate for most of our life with a set of expectations about what will happen, what will be said and done, and how other people will behave. These expectations are based on clues given by place, dress, tradition, conventions, stereotypes and our previous experience. Life would be pretty impossible if we couldn’t operate that way, if we had to make decisions from scratch about how cope with all the different experiences that face us every day as with live in our families and in the world.

But those expectations don’t operate on the Jericho road.

They don’t operate because the Jericho road exists in the world of the parable – and the parable faces its hearers with a situation which turns all their previous expectations upside down.

Some Biblical scholars have made it their life’s work to try to find the authentic words of Jesus: those words which Jesus actually spoke, rather than those which were put into his mouth by the preachers and teachers of the Early Church. Most of the arguments and dialogue with his opponents, like the conversations with which Luke surrounds the parable of the Good Samaritan are thought not to be authentic, but the additions of the gospel writers. But the parables themselves, with their subversive reversal of expectations, are judged to be the authentic voice of Jesus, a voice which proclaims the values of the Kingdom, and in doing so redraws the map of the social and religious world in which we operate.

And the Jericho road is one of the most important places on that map.

The Jericho road is a dangerous place and a frightening place. On the Jericho road there are no rules, no boundaries and our stereotypes have no foundation. On the Jericho road, everything is turned upside down. And this is because, on the Jericho road, we meet God, and we must operate by God’s values and according to God’s expectations.

The lawyer who asked Jesus questions about how to inherit eternal life thought he knew how to travel the Jericho road. He thought it was a matter of following the religious rules and knowing all the right definitions. But those rules and those definitions prevented him from actually encountering God. The parable, which was Jesus’ answer to his questions, broke through all those neat definitions of a ‘neighbour’ that centuries of rabbinic refinement had constructed, definitions that excluded anyone who wasn’t Jewish, anyone who didn’t keep a host of nit-picking rules, anyone who wasn’t conventionally religious.

The lawyer who asked Jesus questions about how to inherit eternal life thought he knew how to travel the Jericho road. He thought it was a matter of following the religious rules and knowing all the right definitions. But those rules and those definitions prevented him from actually encountering God. The parable, which was Jesus’ answer to his questions, broke through all those neat definitions of a ‘neighbour’ that centuries of rabbinic refinement had constructed, definitions that excluded anyone who wasn’t Jewish, anyone who didn’t keep a host of nit-picking rules, anyone who wasn’t conventionally religious.

The parable overturned the expectation that the first duty of a religious functionary was to keep himself pure and undamaged for the performance of religious rites. The parable reversed the stereotype of the Samaritan as one who would react to an injured Jew with hostility. For in the parable, the Samaritan plays the role of God, and as God, he reacts to the situation with compassion.

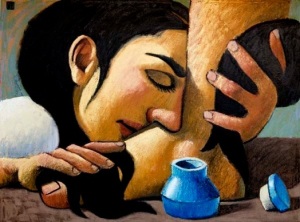

‘Compassion’ in English is a fairly bland word. But as used of God, it has an enormous depth of meaning. God in the Old Testament is a God of ‘hesed’ a Hebrew word for which there is no adequate English translation. As well as compassion it includes love, kindness, faithfulness, tenderness, consistency, pity, dependability and humanity. But above all it involves a passion that our nice English translations fail to convey. When God looks down on wayward humanity, when the Samaritan sees the wounded man on the Jericho road they are filled with an emotion that is gut-wrenching in its intensity. It is an emotion that knows no boundaries of race, tribe, religion, gender or status. It is an emotion which puts human need first, and an emotion that demands action.

And the parable of the Good Samaritan tells us that, if we want to experience eternal life, we ordinary people must feel as God feels, and act as God acts, whenever we find ourselves on the Jericho road.

One of the problems with parables is that we tend to take them too literally. So we apply the teaching about helping our neighbour only in situations of physical danger, we update the parable in terms of mugging and road accidents, we change the good Samaritan into a person of another race, or class – or the supporter of a rival football team. Of course, we might find ourselves on the Jericho road on a real road, as we drive along or walk to school. But it won’t necessarily be so. We could find ourselves on the Jericho road anywhere, at any time, in any situation when we are faced with a decision that calls upon us to show God’s compassion to our fellow human beings.

For the Jericho road runs through our daily lives, through our homes and our schools and our workplaces. We are on the Jericho road whenever we have to choose to act, or stand by and do nothing, to say something or keep silent; whenever we vote, whenever we have to respond to a planning application that might affect our comfort or the value of our property, and whenever we shop and have to make decisions about whether to go for the fairly traded or environmentally friendly option or for the cheapest and most easily available one. In all these situations we are asked by Jesus’ parable to recognise that people we have never met, people who are totally unlike ourselves, people in need are our neighbours in the Kingdom of God.

The Jericho road runs straight through the Church, and we are on it whenever we are tempted to become a tribal church, accepting only ‘people like us’ into membership, instead of being the holy and catholic church that we proclaim ourselves to be in the creed. It is a major tragedy that so often we in the church fail to recognise that we are on the Jericho road when we make our decisions about how our church life is to be organised – and that so often we become the priest or the Levite, and walk by on the other side.

We who call ourselves Christians are always on the Jericho road. And our God of compassion is constantly giving us fresh opportunities to be the good Samaritan, to become a neighbour to the one who fell among thieves. For Jesus came to teach us that eternal life is not something you earn by obeying the rules, or living a cosy life of being nice to the deserving poor. Eternal life is something we live, day by day, as we take decisions and act on them.

Jesus invites us, every moment of our lives, to set out on the dangerous and difficult journey on the road to Jericho. He asks us to be at home in a different world, in a world turned upside down, where a Samaritan knows more about the God of Israel than a priest and a top religious lawyer. He invites us into a world where religion is about what we do every day of the week, not about what we do on Sundays.

He invites us to leave the safety of Jerusalem and travel the Jericho road, so that we may meet, in the guise of the Good Samaritan, our God of passionate compassion. And he promises us that, if we do, there on the Jericho road we will find ourselves inheritors of eternal life.

Be (Un)Prepared!

July 7, 2013

Isaiah 66, 10-14; Galatians 6, 1-16; Luke 10 1-11.

I recently read a story online about a couple and their daughter who emigrated from Hull to Australia after watching a TV documentary about the luxurious life there – and then returned to the UK two months later because of the high cost of living they encountered, the difficulty of getting their favourite foods, and missing their families. It cost them £10K to move to Australia – and now they are back without their furniture, and without a permanent place to live.

I just can’t imagine making a major decision like moving house, let alone moving continents without a lot of research beforehand. Even when we go on holiday, we look up hotels on TripAdvisor and make sure we have somewhere to stay; we make lists for what we pack, and plan out routes before we set off.

So, the Gospel passage for today, which has been described as ‘The Owner’s Instruction Manual for Christian Mission’ is really rather daunting for me. I tend to follow the Scout motto ‘Be Prepared’, but this passage seems to be saying “Be UNPrepared”. It seems to go against everything that our society regards as sensible – planing things out, taking out insurance, making sure you’ve got the resources to finish something before you start, relying on yourself and your abilities, and so on. What is God saying to us through this passage?

This passage comes in the second half of Luke’s Gospel, after the Transfiguration, when Jesus has set his face towards Jerusalem. It parallels the sending out of the 12 Apostles in Luke 9, and reflects Luke’s special interest in mission to the Gentiles (in the Bible 12 is the number of Israel and 70 or 72 the number of the whole earth). So this passage is telling us about the wider mission of the church.

Jesus doesn’t minimise the challenges of mission activity – then, as now there will be plenty of resistance to the Good News, fuelled by fear, by indifference, by self-interest as the message of the coming Kingdom challenges the prevailing power structure. Jesus warns his disciples that they will be going as “sheep among wolves”. He warns them that the work will be hard: “The harvest is ready but the workers are few”. He doesn’t give them impossible targets; their job is simply to prepare the ground for his arrival. They are to speak words of peace, heal the sick and announce the imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God. The implication is that he will do the rest, building on their preparatory work, when he comes.

Some of the instructions Jesus give seem familiar to us as we plan church activities. First of all he instructs his disciples to pray – but the prayers are not for success, but for each other, and for more and more people to become involved with the work of mission. That’s a good reminder for us that mission is not the work just of the ordained, or of trained mission workers, but of every Christian.

Second, Jesus instructs them to go out in pairs, a sensible instruction when we go out into hazardous environments; but it’s not just about our personal safety – it reminds us also that we are part of a Christian community, made up of members with many different skills and talents, all of which may be useful in bringing different sorts of people into fellowship. In today’s world, when there is so much cult of personality, we tend to focus on individuals and what they achieve; it is all to easy to forget the people who support and co-operate with the front line workers, and so play their part in the harvest of mission. The church has tended to do that too: this story is a useful counter to that. We know the names of the 12 apostles who were sent out, and have made them into saints, and named churches after them. We don’t know anything about these 70 or 72 disciples, not even their names. They stand for the thousands, even millions of faithful Christians who have worked to bring in the Kingdom of God throughout history and continue to do so now.

Jesus also gives them a script to follow. He tells them what to say: “Peace be on this house. The Kingdom of God has come near to you.” It’s a very simple slogan – short, to the point, affirming. It would even fit into a Tweet!

Modern evangelism courses often try to equip ordinary Christians with a script; but they are rarely as simple and affirming as that. How often have Christians gone into situations speaking words of peace and affirmation? If you look at the media today, the impression given is that Christians are against things and people, and condemn rather than affirm. Perhaps we would do better at bringing in the Kingdom if we went back to Jesus’s script!

These instructions are easy to follow. It is the rest of the manual that goes against our instincts. Every mission initiative that I’ve heard about has involved lots of preparation, lots of expenditure and lots of equipment. But Jesus says: take nothing with you, not even any money, rely on strangers for food and accommodation, accept whatever you’re offered without complaint – in short, travel light!

That might have seemed less strange in Jesus’s time than it does now. Hospitality to strangers was a social obligation in Biblical society in a way it is not for ours. To mistreat visitors brought condemnation of the harshest kind. Later, in a continuation of the passage that we don’t get in the lectionary, Jesus says that it will be better for the town of Sodom on judgement day than for any town that rejects his disciples, reminding us that the sin of Sodom had nothing to do with homosexuality – it was mistreatment of strangers and abuse of hospitality that brought punishment and destruction upon them, not gay sex.

What was Jesus really saying to the disciples with these instructions? I think he was asking them to rely on God, and not on themselves. In our Old Testament reading, through the words of the prophet Isaiah, we hear God’s promise that he will nurture those who serve him as a mother nurtures her children, and protect them as they would be protected in a walled city like Jerusalem. It is that sort of total trust that Jesus asked of his disciples and asks of us. He asks them to make themselves vulnerable when they are engaged in evangelism – and he asks the same of us. He tells them to eat whatever is put in front of them; that would have been a much harder instruction for observant Jews, with their complex food laws, to accept than it is for us, but it reminds us that we are instructed to rely not just on those who are like us, but also, perhaps on those from a very different culture and with very different tastes from those which the Church has traditionally endorsed.

So how do we interpret these instructions for mission in today’s world? I don’t think it is really telling us to be unprepared in the sense of not spending money or using modern equipment with us when we engage in mission. But it is telling us to keep things simple and to concentrate on the essential of the Christian message and not get sidelined onto peripheral things. It reminds us that often it is the small things, not the grand gestures that advance the Kingdom – things like speaking words of peace and comfort, bringing healing into a tense situation, accepting the hospitality of those different from us, and not making a fuss when things are not done as we think they ought to be done. And things like helping at a foodbank, buying Fairtrade goods, twinning your toilet, or demonstrating for peace and justice.

It reminds us that we must be prepared to work with all sorts of different people to build the Kingdom; in our society that might include government agencies, atheists and humanists and even people of other faiths.

Above all it reminds us that the only equipment we need for mission is trust in the grace of God revealed through the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. This is the message that Paul gives to the Galatian Christians in the letter from which our Epistle reading came. He is advising them to rely on the Holy Spirit, and to live a life based on mutual love and service, rather than relying on the keeping of the Jewish law to bring them salvation. He acknowledges that this path will not be easy: it led Christ to the cross, and may well lead his followers to the same place, but it is the only way to serve God faithfully. What Christ’s followers must trust in is not their own individual talents, or earthly power-structures or miraculous demonstrations, but in God’s commitment to peace and justice, which will ultimately prevail.

So, however little it may seem we have available to us to fulfil the missionary task that Jesus gave us, we are not really unprepared. As Paul assures us, doing what is right, working for the good of all, trusting in the way of the cross will bring the harvest and bring in the new creation for which we hope.

Power of the Holy Spirit

June 11, 2013

Power of the Holy Spirit

Assembly for KS 1 & 2, comparing the power of electricity with the Holy Spirit

Aim: To show that the Holy Spirit has always been at work in the world, but was known in a new way at Pentecost.

Bible Passage: Acts 2, 1-8

Preparation and materials:

You will need several devices that work by electricity – some with batteries and some which plug in to power source.

You will need to know something of history of harnessing of electricity.

http://www.wisegeek.org/who-discovered-electricity.htm

Assembly

Ask what powers all devices? Electricity. If not connected to it, (by plug or battery) won’t work. Expand that electricity used to help us keep warm (fires) do difficult tasks (power tools) help us see and communicate (phones, radios etc.)

Ask who invented electricity? You may get several answers, including that no-one invented it, but several people discovered how to harness it and use it.

If appropriate give brief history of use of electricity.

Emphasise that electricity a natural force, in the universe since the very beginning of time, which humans became aware of and able to use .

Tell the story of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit came upon friends and followers of Jesus with great power, enabling them to do things they couldn’t do before, to communicate Good News of Gospel to all sorts of different people, and giving them comfort when they were in trouble.

Point out that power of Holy Spirit in some ways like power of electricity.

Say Holy Spirit came in renewed strength at Pentecost, but had always been at work in world. Bible tells us that Spirit active in creation of world, animals and humans, and inspired words of prophets who taught Jews about God before the coming of Jesus. Also there at Annunciation when Mary told she would have Jesus and at baptism of Jesus.

Say Christians believe they need to be open/ connected/ plugged in to Holy Spirit in order to do the work in the world that Jesus did, and which he taught them God wants them to do also

Time for reflection

Switch on a torch/ electric light.

Jesus’s disciple John said he was the Light of the World. The Holy Spirit gives power to his followers to be light like him.

Think how you can be like a light to people around you today.

Prayer:

Dear God,

We thank you that your Holy Spirit is always at work in your world,

bringing strength and comfort, words and light to those who receive it.

Through your Spirit, help us to live as Jesus did,

to bring light to your world,

and to live in the way that you want us to live.

Amen

Outside In!

June 2, 2013

Ordinary 9. Proper 4C

1 Kings 8,22-23 & 41-43; Galatians 1,1-12; Luke 7, 1-10

Last weekend there were a number of demonstrations against Islamic extremism in reaction to the murder of Drummer Lee Rigby on the streets of Woolwich the previous Wednesday. There was a march through the centre of London on Bank Holiday Monday organised by the English Defence League and also in Newcastle on Saturday and York on Sunday. These came after 10 mosques around the country had been subject to arson or graffiti attacks and there had been a further 193 anti-Muslim incidents reported to the police.

In Newcastle , a prominent Muslim political and social commentator, Mo Ansar, confronted the EDL leader, Tommy Robinson, but at the end of their discussion was photographed with a smile on his face, being hugged by the person whose policies he opposes. For this he was criticised by many Muslims and anti-fascists, for compromising with the promotors of prejudice and evil. When they learnt that the EDL march was targeting their mosque in York, its leaders decided to have an open day. Helped by members of other faith communities, they served tea and cakes to the marchers, invited them into the mosque for discussion, and played an impromptu game of football with some of them. The Archbishop of York praised them for meeting anger and hatred with peace and warmth.

In each of these incidents, those who followed a faith refused to treat a non-believer, and those who oppressed and harassed them as ‘outsiders’. They opened themselves up to them and invited them to become, in some sense, ‘insiders’.

This is the message that we are meant to hear from our Bible readings today.

The passage from 1 Kings is part of the description of the dedication of Solomon’s Temple. Unlike the later Temple, built after the exile and expanded by Herod the Great, the first Temple did not have different courts and barriers to keep Gentiles and women away from the central sanctuary. Solomon’s speech showed that he hoped his magnificent Temple would become a place of prayer to the one true God for people of every nation. Its magnificence would draw people to become insiders.

In the reading from the letter to the Galatians, we hear one half of a correspondence between Paul and the church he established in Galatia, which consisted largely of Gentiles.

After he had left, it seems, Jewish Christians visited the churches, and insisted that, before they could truly become Christians, the pagan converts had to subject themselves to Jewish ceremonial law, including, in the case of male converts, circumcision. This appalled Paul, who taught that everyone was equally welcome as a Christian through the grace of God in Christ, regardless of their previous background, and that no action was needed apart from an acknowledgement of Jesus as Lord.

The challenge to treat all people as insiders in the name of Jesus is brought out most strongly in the story of the healing of the centurion’s servant, which we heard in today’s Gospel. This was clearly an important story to the early Christian community; there are slightly different versions of it in three of the four gospels (Matthew, John and Luke).

The centurion was in more than one way an outsider for Jesus and his companions. He was a Gentile; entering his house, eating with him, having any physical contact with him or his possessions would have rendered an observant Jew ceremonially unclean. He would not have been allowed to approach the holiest part of the Jerusalem temple; he would have been confined to the outer Court of the the Gentiles.

Then, he was a Roman soldier, a representative of the hated enemy that was occupying the sacred land of the Jews. There had been a large military presence in Galilee since the uprising that followed the death of Herod the Great in Jesus’s early childhood; an uprising that led to savage reprisals and multiple crucifixions, events that were still raw in the memory of many of Jesus’s fellow Galileans. The rebellion centred on Sepphoris, four miles north of Jesus’s home town of Nazareth. After the rebellion was crushed, Sepphoris was razed to the ground and its inhabitants taken into slavery. Roman legions remained in the area to deter any further rebellion, and the centurion was part of this army of occupation; it is possible the slave was a Jewish child, taken into slavery after the rebellion.

Any Zealot would have taken the first opportunity to kill the centurion. Religious Jews would have seen him as a representative of the ‘principalities and powers’ against which the faithful believers should struggle.

Third, the anxiety and effort which the centurion expended over the healing of his slave implies that the relationship between them was more than that of master/servant. This was something that was quite accepted in Roman society; but the Jews saw such homosexual relationships as evidence of the depravity of Roman society and further proof of its alliance with evil.

Yet the centurion did not act like an outsider. He did not keep the usual distance between occupier and occupied. He did not automatically treat every member of the subject people as a potential terrorist. It is possible that he was a “God-fearer’, a Gentile who was attracted to the ethical teaching of Judaism, but who would not go the whole way and become a convert. Luke reports he had paid for the construction of the synagogue, and he was friendly enough with the elders to ask them to approach Jesus on his behalf. He was sensitive to Jewish religious beliefs – although he wrapped it up in comparisons between his own authority and that of Jesus, his second message was designed to avoid placing Jesus in the position of becoming unclean by entering a Gentile house.

And although he was a member of the occupying power, he asked for help from a Jewish holy man. He treated him with respect, using the honourable title ‘Lord’. This was an amazing act of humility – equivalent to a member of the British Raj asking for help from a Hindu Sadhu or a colonial official in Africa approaching a witch doctor.

The Roman centurion didn’t act like an outsider – and Jesus didn’t treat him like one. He responded immediately to his request, seems to have been prepared, as on other occasions to risk making himself ritually unclean to help, and commended his faith as being greater than that of any insider.

This story anticipates the inclusion of Gentiles inside the community of the redeemed that we read about in Paul’s letters and the book of Acts. It highlights the irony, that the Jewish leaders failed to recognise the authority of Jesus – but a Gentile outsider did, and was commended for it. In the end, the healing of the servant was not important. The important thing is the greater healing proclaimed in this miracle – the healing of the barriers against a hated and excluded group, who are now included.

The Roman centurion would still be considered an outsider by some in our society today: the wrong religion, the wrong nationality, the wrong sexuality.

Our world today seems to revel in dividing itself into hostile groups based on many different characteristics. We love to label people according to their race, colour, religion, gender, sexuality, country of origin, location within the country, political affiliation, and so on and so on; and give that as a reason to justify competition, conflict and exclusion. Even locally, even within one faith, we can separate ourselves from others on the basis of differences of interpretation of faith and churchmanship.

Today the scriptures challenge us to reject the worldly way of building up our own ‘insider’ identity by hostility to those we label ‘outsiders’. It tells us that, to the God revealed in Jesus, there are no outsiders. God is the God of all people and all creation, both those who worship as we do, and those who don’t, those who identify themselves as believers and those who don’t. Our Spirit inspired mission is to invite the turn the world outside in, to invite the outsider in and offer acceptance and healing, knowing that in the all encompassing love of God, there are no outsiders.